זֶה אֵלִי וְאַנְוֵהוּ

This is my God and I will glorify Him.

Growing up, I was largely unimpressed with Judaica. I got four kiddush cups for my bar mitzvah, every one of them baroque. Once I saw someone use a pair of elegant blue blown glass candlesticks for Shabbat and wondered why everything at the Judaica store was either straight out of 19th century Vienna or totally kitschy. During the course of my research into Hebrew typography, I discovered a lost world of Jewish arts and craft, one that inspires me in my quest to make Jewish work that is rooted in history but is still new and relevant today. There’s so much history here, and so much wonderful typography!1

The rabbis of the Talmud saw the above quoted verse in Exodus and expounded on it.

”זה אלי ואנוהו“ התנאה לפניו במצות עשה לפניו. סוכה נאה, ולולב נאה, ושופר נאה, ציצית נאה, ספר תורה נאה, וכתוב בו לשמו בדיו נאה, בקולמוס נאה, בלבלר אומן, וכורכו בשיראין נאין.

“This is my God, and I will glorify Him” means glorify yourself before Him in the fulfilment of mitzvot. Make a beautiful sukkah in His honor, a beautiful lulav, a beautiful shofar, beautiful tzitzit, and a beautiful sefer Torah, and write it with fine ink, a fine reed pen, and a skilled penman, and wrap it with beautiful silks.

—Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Shabbat 133b2

This is the root of the concept of Hiddur mitzvah (הידור מצווה), beautifying the service of God. Peter S. Knobel elaborates:

The Midrash suggests that not only are mitzvot enhanced by an aesthetic dimension but so is the Jew who observes it… There seems to be reciprocity of beauty through the agency of mitzvot: the Jew becomes beautiful as he/she performs a mitzvah. “But, conversely, Israel ‘beautifies’ God by performing the commandments in the most ‘beautiful’ manner…”

—Gates of the Seasons: A Guide to the Jewish Year, 1980, quoting Claude Goldsmid Montefiore and Herbert Loewe, A Rabbinic Anthology, 1938.

Shabbat candlesticks by Ludwig Wolpert with text from the prayers welcoming Shabbat: “Come, let us sing unto the Lord. Let us exult before the Rock of our salvation” (Psalm 95:1). Photo via.

What a powerful concept, that not only is physical beauty a meaningful addition to religious service, but by obliging we are improving ourselves. We should not be content to build our sukkah to the bare minimum of the Mishnah’s construction guidelines; this is an opportunity to rejoice in the practice of Judaism through artistic excellence. But I’m not an artist, you say. I can’t sculpt a kiddush cup! Let’s look again to Exodus as the Israelites begin the construction of the mishkan.3

“See, the Lord has called by name Bezalel … And He has filled him with the spirit of God, in wisdom, in understanding, and in knowledge, and in all manner of workmanship. And to devise skillful works, to work in gold, and in silver, and in brass, and in cutting of stones for setting, and in carving of wood … And Bezalel and Oholiab shall work, and every wise-hearted man, in whom God has put wisdom and understanding to know how to work all the work for the service of the sanctuary, according to all that God hath commanded.” And Moses called Bezalel and Oholiab, and every wise-hearted man, in whose heart God had put wisdom, even every one whose heart stirred him up to come unto the work to do it.

—Exodus 35:30-36:2 (quoting Exodus 31: 1-5)

Bezalel was the first Jewish artist. He was tasked with spearheading construction of the mishkan, and he crafted the ark, and altar, and table, along with his assistant Oholiav, an engraver and embroiderer.4 How were these men so skilled? Their talent was not innate but was imbued in them by God Himself to be useful in divine service. Each person came to assist in the construction with their own skillset — metalworking, carpentry, needlework, and so on — all of them with unique God-given talents. Oholiav is referred to as חֹשֵׁב, often translated as “artist” or “designer” but coming from the root “think.” For it’s not always about having abilities; it’s the ability to understand how to use what you know.

Mosaic floor of the Beit Alfa synagogue near Beit She’an in northern Israel, dating from the late fifth century. Read more about synagogue decoration and other large-scale Jewish arts here.

“Carpet page” from the Burgos Bible, also known as the Damascus Keter, written in Burgos Spain, 1260. See the whole manuscript here.

The Temple in Jerusalem was described (or more accurately, self-described) as the most beautiful building in the world. A small pomegranate made of hippopotamus ivory could be the only extant relic dating to the First Temple, making it the oldest “Jewish art” known. (I’m defining Jewish art as art — a word that could use a definition of its own, but here describing objects created with the intention of being art — made by Jews for a Jewish purpose or utilizing Jewish content. It’s possible this ivory pomegranate came from another Semitic cult, or is even a forgery.) Many more artifacts exist from the Second Temple period, including architectural elements, ossuaries, and drawings on stone. Decorating places of worship continued after the destruction of the Temple, as famously seen in the murals of the Dura Europos Synagogue (Syria, 244 AD) and the mosaics of the Beit Alfa synagogue (above) and others in northern Israel.

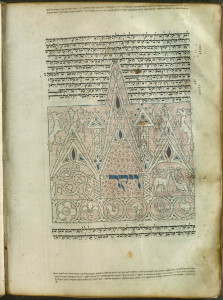

Micrographic design for the opening of Vayikra (Leviticus) from the Ebermannstadt Pentateuch, Ebermannstadt, Germany, 1290. See the whole manuscript here.

Jews love their books, and by the tenth century they were embellishing them with ornate designs both original and inspired by their locale. (See more typographic illuminated manuscripts in my entry on haggadot.) It has even been suggested that illuminated manuscripts arose from the tradition of synagogue art. Jews in Muslim lands appropriated the style of Arabic ornamentation, creating elaborate geometric designs and using text as a design element. At the time, bibles were copied with marginal notes called the Masora, and over time the practice developed of creating designs with the text of the Masora written very small. These designs, called micrography for “tiny writing,” became more and more ornate, from simple shapes to scenes with animals and buildings. The tradition spread to Ashkenazi Jewry, who turned micrography into a stand-alone art form that persists to this day.

Shiviti plaque on paper from Spain or North Africa(?), late 19th or early 20th century. Via

Following the rise of Kabbalah in the 13th century, scholars tried to makes sense of the divine architecture of the universe by drawing cosmological diagrams describing the relationships of the emanations of God. Called ilanot, these diagrams also became increasingly complex, with trees within trees, integrating carmina figurata (text in the shape of objects) and micrographic drawings of the biblical menora. Soon menorot became a genre of their own. Constructed out of Psalms 67, whose seven verses construct the seven branches of the lamp, the menora was crowned with another verse: שִׁוִּיתִי יְהוָה לְנֶגְדִּי תָמִיד (I have God before me at all times) from Psalms 16:8. The shiviti, as it is known from that verse, functioned as an object of meditation, and was often placed before the reader’s stand in the synagogue and in prayer books. Ilanot and shivitis were ascribed magical powers in and of themselves, and despite rabbinic prohibitions, were used as amulets to ward off the evil eye and prevent everything from illness and miscarriage to wayward children. In the 19th century, shiviti plaques made in Hebron were exported as souvenirs of the holy land, imbued with the mystical holiness of the place.5

German pewter plates, 18th century. From left, a Purim plate, a shiva plate, and a plate for meat. Via

Turning to ritual objects, we can divide them into two groups: those created by specialized craftsmen and those created by folk artists. What I love about Jewish folk art is that these often anonymous artists used whatever tools and materials available to them to show their Jewish devotion. Fancy pewter plates were in vogue in 18th century Germany,6 and Jews, too, would customize their pewter plates for any important occasion involving eating: Shabbat, Passover, Purim, even shiva! Your family’s tacky Chanuka serving dish and matzah plate do not even compare.

Shevuoslech from Poland, of the papercuts smuggled out of Europe by Giza Frankel. Via

Shavuot has always been the neglected child of the Jewish holidays, not having any fun rituals or items like Sukkot, Passover, or Rosh Hashana. This was not the case in Eastern Europe in the 18th and 19th century, whose Jews had the tradition of cutting Shavuoslekh,7 or Shavuot-themed papercuts, and hanging them in the windows. Papercutting had been a Jewish folk art for centuries, requiring little beyond a knife and paper, and was in fact predominantly a craft of men. These papercuts were often painted in bright colors and glued onto contrasting dark paper to show off the details. Papercuts were also made for mizrach signs indicating the eastward direction of Jerusalem, shivitis, mystical protection, and pure decoration. As you can imagine, the pieces were very fragile, and compounded with the destruction of Eastern European Jewry, not many of them survive today.

A recent trend has been the styling and theming of mishloach manot (or shalach manos in Yiddish) on Purim. It is customary to give gifts of food to neighbors and friends on the holiday, and many take the opportunity to assemble fun packages as a creative religious outlet. (And some, apparently, think the trend has gone too far.) The last few years, I’ve been designing mishloach manot packages of my own out of cut paper with typographic flourishes. Marian Bantjes makes Valentine’s cards. I make Purim boxes.

My mishloach manot boxes from Purim 2015. One side of the horse has a Purim message from me incised into the paper, and the other side features a quote from the book of Esther (6:11): “Thus shall be done to the man the king wishes to honor,” obligatorily declared by Haman as he parades Mordechai through the streets of Shushan on horseback. It’s made of papercut black cardstock with lollypop legs. It’s too small to fit much else besides some nuts or candies, but it’s what’s on the outside that counts, right? See more photos and previous years’ boxes here.

Shiviti plaque by Zelig Segal. Via

Modern artists and craftspeople have continued experimenting with these ideas. Ludwig Wolpert (1900-1981) crafted some of the most incredible typographic metalwork I have ever seen. Utilizing the clean lines of the Bauhaus style with Hebrew texts, his candlesticks, mezuzot, and iron gates look just as fresh today as they did eighty years ago. I included one image above. Look him up for so many others.

One of my favorite contemporary pieces is the shiviti by Zelig Segal shown here. He’s written the verse and placed it behind the word “shiviti,” which is itself cut out of the metal. In this way he’s drawing on old artistic traditions and subjects to make something very new.

How do the artists themselves approach Jewish work? “I am but a Jew praying in art,” wrote Arthur Szyk in his haggadah. Writes David Moss, “The making of Jewish art can be a holy process. The intensity, thought, care and devotion one expends in other spiritual matters can be applied to art as well.” To them, creating art for Jewish service is its own form of Jewish service. And if their talents are indeed God-given, not using them may even be a rejection of God. With that in mind, how can anyone not create?

There is a piyyut in the Yom Kippur evening liturgy that always spoke to me. It begins:

כִּי הִנֵּה כַּחֹמֶר בְּיַד הַיּוֹצֵר, בִּרְצוֹתוֹ מַרְחִיב וּבִרְצוֹתוֹ מְקַצֵּר. כֵּן אֲנַחְנוּ בְיָדְךָ…

Like clay in the hands of the potter, he expands it and contracts it at will. So are we in Your hand…

—author unknown

It then continues to compare man to a range of materials with God as the artist:

Like the stone in the hand of the cutter…

Like the ax-head in the hand of the blacksmith…

Like the glass in the hand of the blower…

Like the curtain in the hand of the embroiderer…

Like the silver in the hand of the silversmith…

I was interested in this poem from a young age simply because it cast God in a context meaningful to me. But there is a much deeper precedent for thinking about God in this way.

וַיִּבְרָא אֱלֹהִים אֶת הָאָדָם בְּצַלְמוֹ, בְּצֶלֶם אֱלֹהִים בָּרָא אֹתוֹ.

So God created Mankind in His own image, in the image of God He created him.

—Genesis 1:27

If God is the creator of the universe, and man was created in His image, then man’s role is also that of creator. It is how we reflect the divine. In anthropology, what separates man from animals is the abstract thinking required to use tools to make tools. Creation is our defining characteristic.

Hiddur mitzvah improves our experience of ritual performance, fulfills our purpose of being human, and brings us closer to the divine. So go find a beautiful haggadah with great pictures. Prepare magazine-worthy spreads for Shabbat meals. Use your talents to create Judaica meaningful to you, or find some that speak to your tastes. Get your family involved. Make memories that you will carry with you and pass on to future generations. Together, we will glorify.

Notes

| ⇧1 | This essay is adapted from a lecture given at Temple Aliyah on March 26, 2015 as part of their Experiments in Spiritual Expression Adult Learning Series. |

| ⇧2 | A similar sentiment by Rabbi Ishmael with a slightly shorter list appears in Midrash Mechilta, Shirata, chapter 3:

ר׳ ישמעאל אומר, וכי אפשר לבשר ודם להנוות לקונו? אלא אנוה לו במצות אעשה לפניו: לולב נאה, סוכה נאה, ציצית נאה, תפלה נאה. Is it possible for a human being to add glory to his Creator? What this really means is: I shall glorify Him in the way I perform mitzvot. I shall prepare before Him a beautiful lulav, beautiful sukkah, beautiful tzitzit, and beautiful tefilin. |

| ⇧3 | AKA the Tabernacle. Which is a fantastic word. |

| ⇧4 | When artist Boris Schatz founded an art school in Mandate Palestine in 1906, he named it the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts. It is now the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. |

| ⇧5 | There is so much fascinating Kabbalistic design out there. Hopefully that will be the subject of forthcoming essays. |

| ⇧6 | And are still used today as commemorative pieces. Read more than you’d ever care to know about pewter in Pewter Plate: A Historical and Descriptive Handbook by Henri Jean Louis Joseph Massé. |

| ⇧7 | Meaning “little Shavuot” also called shevuosim or shevuosl, or royzelech, meaning “little roses.” |

Hello Hillel:

Your post on Hebrew type is delightful and informative. Thanks for saying what needed to be said about art that happens to be Jewish and for providing the origin of hiddur mitzvot. I enjoyed reading about your outdoor art installation projects in LA and Tel Aviv! Though I’ve done some public commissions here in Pittsburgh where I am based, I am an primarily an artist/illustrator/writer and designer who, like you, specializes in Judaic themes. In the interest of sharing, I thought you might like to know of my work as well; in particular, two books: Between Heaven & Earth: An Illuminated Torah Commentary (Pomegranate, 2009) and An Illumination Of Blessings (Imaginarius Editions, 2014). Here are links:

http://magiceyegallery.com/BookPage.aspx?id=1

http://magiceyegallery.com/BookPage.aspx?id=2

I wish you best of luck on your own work and look forward to your comments and questions.

Ilene

I am sure I had mentioned this before, but I have an autographed print of the United States by Arthur Szck and Arthur Jaffe. I took a picture of it, but I have to email it to your attention. My business was located at 3 East 28th Street in NYC, until 1981, when we moved to 22 W. 19th Street. Arthur Jaffe Heliochrome Printers probably printed some of Szck’s works. Jaffe was born in 1884 and I met him when he was about 90 – circa 1973-4. I am curious if it has any special value, or whether you know anything about Jaffe.

Richard J. Garfunkel