וּסְפַרְתֶּם לָכֶם מִמָּחֳרַת הַשַּׁבָּת, מִיּוֹם הֲבִיאֲכֶם אֶת־עֹמֶר הַתְּנוּפָה; שֶׁבַע שַׁבָּתוֹת תְּמִימֹת תִּהְיֶינָה

And you shall count for yourselves from the morrow after the day of rest, from the day that you brought the omer of the wave offering; seven complete weeks shall there be.

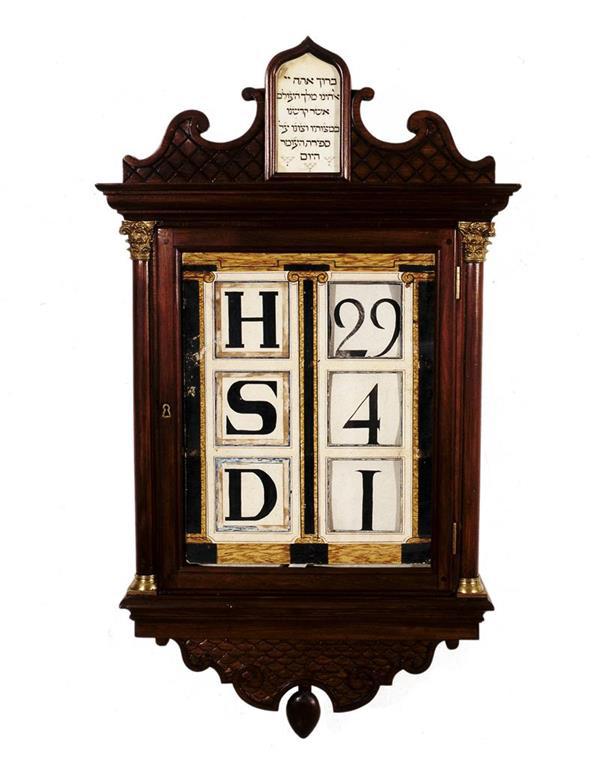

Dutch-Portuguese-style 3-row Omer Counter. H is Portuguese for homer (omer); S for semanas, “weeks,” and D for dios, “day.” See more of this kind of counter here and here.

Previously, I wrote about the concept of hiddur mitzvah, incorporating physical beautify into ritual observance. We are now in the midst of an oft-overlooked and unappreciated ritual, but one that has great artistic potential: Sefirat Ha-Omer, the Counting of the Omer. We commemorate the lead up to the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai by counting the 49 days from the second night of Passover to Shavuot. We no longer bring the Omer barley offering at the Temple in Jerusalem; instead, the liturgy includes a simple statement every day of what number day it is and how many weeks it’s been thus far. “Today is the forty-seventh day of the Omer, which is six weeks and five days of the Omer.” Thrilling, right? This year, I decided to liven things up a bit with typography.

Continue reading