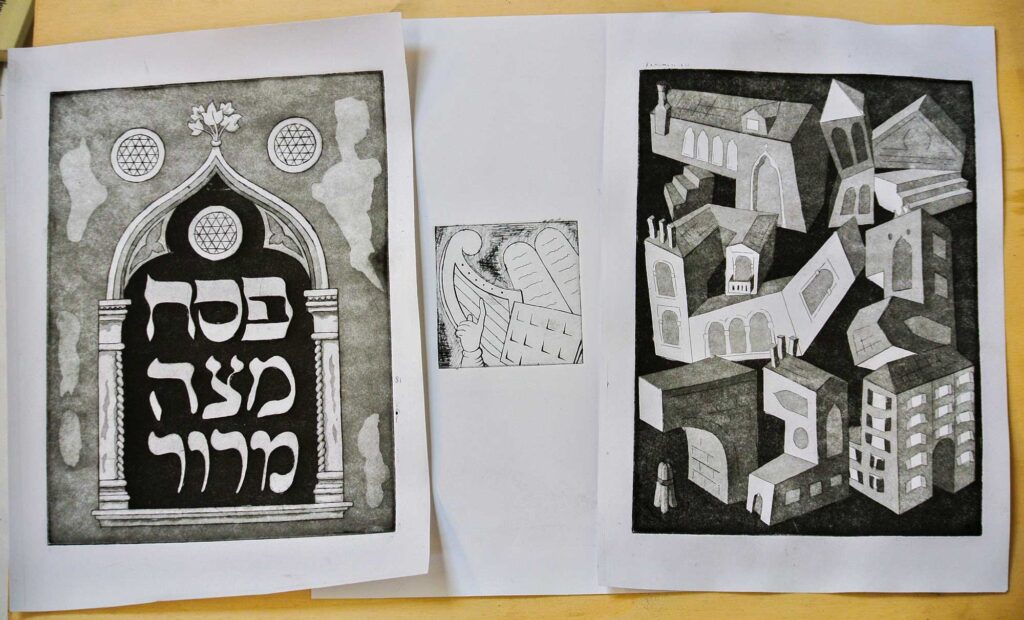

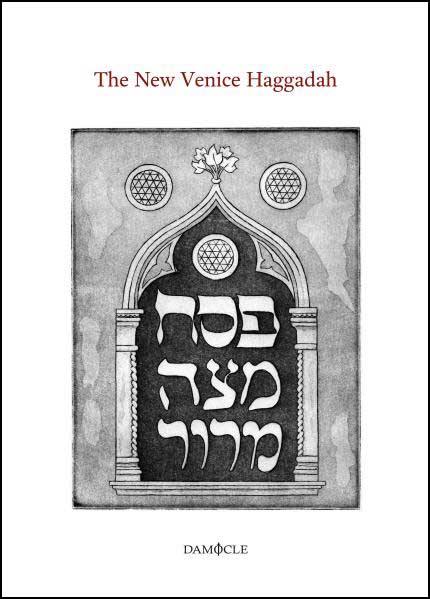

Back in October 2015, I had the immense privilege of traveling to Venice to make art for The New Venice Haggadah. In 2016, Venice, Italy, was to mark the 500th anniversary of the formation of the Jewish Ghetto in Venice, the first ghetto in Europe, founded during Passover in 1516. To celebrate 500 years of Jewish life in Venice, Beit Venezia (formerly the The Venice Center for International Jewish Studies) initiated a year-long series of events, including plays, symposia, and other cultural programs. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Venice was a primary center of Jewish book production. It was there that the first complete Talmud was printed, the first Mikraot Gedolot (a bible with a number of commentaries printed on the same page as the biblical text), and a highly-regarded multi-lingual illustrated Passover haggadah from 1609. In recognition of this history, Beit Venezia invited eight artists from around he world to create new work for a New Venice Haggadah, honoring the city and its distinctive community.

Continue reading